Courtesy of EarthSky

A Clear Voice for Science

Visit EarthSky at

www.EarthSky.org

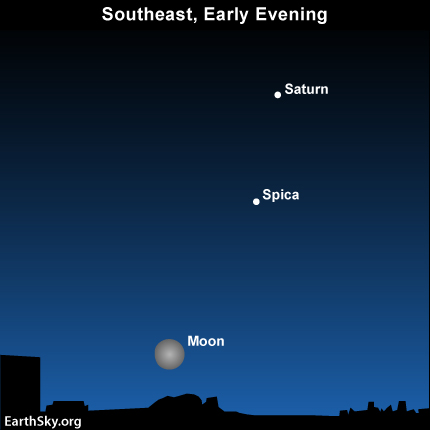

Last night, the full “Egg Moon” was quite close to Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Tonight, however, the moon will be farther away from Spica. Spica appears in the east – below the planet Saturn – at dusk or nightfall, but you may have to wait until early evening to see the waning gibbous moon climbing above the southeast horizon. If you look again in the next couple of nights, you will find the moon even farther from this star. What’s more, you will find the moon rising about an hour later each night.

Last night, the full “Egg Moon” was quite close to Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Tonight, however, the moon will be farther away from Spica. Spica appears in the east – below the planet Saturn – at dusk or nightfall, but you may have to wait until early evening to see the waning gibbous moon climbing above the southeast horizon. If you look again in the next couple of nights, you will find the moon even farther from this star. What’s more, you will find the moon rising about an hour later each night.

Give me 5 minutes and I’ll give you Saturn

Shannon wrote, “Why isn’t the moon in the same place every night when compared to the stars?”

That is a very profound question, one that must have had our ancestors scratching their heads. Thousands of years ago, the answer was thought to be that all celestial objects were fixed to concentric crystal spheres, like the skins of an onion, with Earth at the center of the onion. They thought the moon was fixed to the sphere closest to Earth and so moved separately from the outermost sphere of the stars. That explained – to our ancestors – why the stars stay fixed relative to each other, as the moon moves among the stars.

Today, we envision a universe that extends for billions of light-years in space and time. The visible stars are mostly located tens or hundreds of light-years away while the moon is located only about a light-second away. It is vastly closer to us than the stars. That is why we see it move.

Although we no longer imagine the moon stuck to a crystal sphere, we, like the ancient stargazers, attribute its motion in front of the stars to its relative nearness to us. The moon appears to move in front of the stars because it is so close to us. It moves around our entire sky in one month – the time the moon takes to orbit Earth.

By Deborah Byrd

Astronomy Picture of the Day from NASA/JPL

U.S. Naval Observator Astronomical Information center