Courtesy of EarthSky

A Clear Voice for Science

Visit EarthSky at

www.EarthSky.org

The 2011 Lyrid meteor shower is now picking up steam in the light of the waning gibbous moon. We hear from people all the time who see marvelous meteors in the light of the moon. Still, a dark sky is best for meteor showers, and the moon will drown all but the brightest Lyrid meteors from view this year.

The 2011 Lyrid meteor shower is now picking up steam in the light of the waning gibbous moon. We hear from people all the time who see marvelous meteors in the light of the moon. Still, a dark sky is best for meteor showers, and the moon will drown all but the brightest Lyrid meteors from view this year.

This shower is expected to produce the most meteors before dawn on April 22 or April 23, 2011.

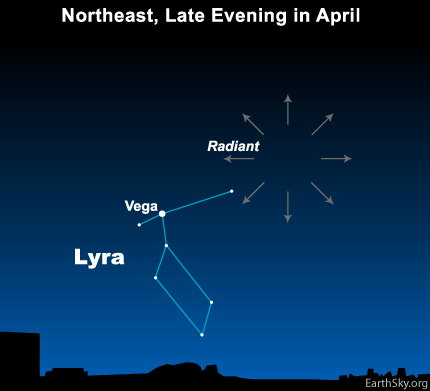

If you do see any meteors, and you trace their paths backwards on the sky’s dome, you’ll find that they appear to originate from a point in the sky near the star Vega, the heavens’ 5th brightest star. The radiant point for the Lyrid shower sits just to the right of Vega, which is the brightest star in the constellation Lyra, the Harp. It is from Vega’s constellation Lyra that the Lyrid meteor shower takes its name.

You do not need to identify Vega in order to watch the Lyrid meteor shower. The idea that you must recognize a meteor shower’s radiant point in order to see any meteors is completely false. Any meteors bright enough to withstand the moon’s bright light will appear unexpectedly, in any part of the sky. They will be most numerous between midnight and dawn on April 22 and April 23.

Why between midnight and dawn? It is because that is when the star Vega – and the shower’s radiant point – is above your horizon. Vega rises above your local horizon – in the northeast – around 9 to 10 p.m. It climbs upward through the night. The higher Vega climbs into the sky, the more meteors that you are likely to see. By midnight, Vega is high enough in the sky that meteors radiating from her direction streak across your sky. Just before dawn, Vega and the radiant point shine high overhead. That is one reason the meteors will be numerous then.

So why near Vega? Why do the meteors radiate from this part of the sky? The radiant point of a meteor shower marks the direction in space – as viewed from Earth – where Earth’s orbit intersects the orbit of a comet. In the case of the Lyrids, the comet is Comet Thatcher. This comet is considered to be the “parent” of the Lyrid meteors. Like all comets, it is a fragile icy body that litters its orbit with debris. When the bits of debris enter Earth’s atmosphere, they spread out a bit before they grow hot enough (due to friction with the air) to be seen. So meteors in annual showers are typically seen over a wide area centered on the radiant, but not precisely at the radiant.

How high up are meteors when they begin to glow?

Could Earth collide with a comet that causes a meteor shower?

The Lyrids are a modest shower at best. In a good year, you will see perhaps 15 meteors per hour. That is in a year when the moon is out of the sky. It contrasts to the year’s best showers – the Perseids of August and Geminids of December – both of which typically produce about 60 meteors per hour in years when the moon is down.

Still, the April Lyrids can surprise you. They’re known to have outbursts of several times the usual number – perhaps up to 60 an hour or so – on rare occasions. Meteor outbursts are not predictable. So – like a fisherman – you must take your lawn chair, a thermos of something to drink, whatever other gear you feel you need – and wait. You will be reclining outside in a dark location, breathing in the night air and gazing up at the starry heavens. Not a bad gig.

Just remember … the moon is not in a good place for this year’s Lyrid meteors. The moon will rise late at night or around midnight, and will stay out for rest of the night. Because the best viewing is usually between midnight and dawn, that means the 2011 Lyrid meteor shower has to contend with a moon-drenched sky. You might be better off to wait until next year. In April 2012, the Lyrids will be moon free!

When is the next meteor shower?

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2011

By EarthSky

Astronomy Picture of the Day from NASA/JPL

U.S. Naval Observator Astronomical Information center

The York County Astronomical Society

I love to watch the skies I am 49 years old and I try to watch every one if posable,every one should watch it it is,will you just haft to see it.And thank the web site that lets us know when to look to the sky.So if you can not sleep watch the sky.The stars have a comming and relaxing felling.